This essay was written early in the planning stages of Galileo’s World (last modified on Oct 10, 2014). For lack of time these ideas were not implemented as planned, but maybe they will be applied somehow in the next exhibit! The closest we came in Galileo’s World to the exhibit design outlined here is our “Top Ten Tours.” This theory of exhibit design shows something of what we were thinking when we developed the “Top Ten Tours,” and it illustrates our thinking of how we would make the exhibition participatory (which, with thanks to Nina Simon, we define as when students and visitors become “co-creators of meaning.” This essay also demonstrates that from the very beginning, we were planning the Galileo’s World exhibit in light of exhibit-based educational outreach. Hope you enjoy it!

What are storylines?

“Storylines” and the dramatic characters which animate them as one journeys through various learning “waystations” are the keys to visitor engagement with a complex, multi-layered exhibition like Galileo’s World.

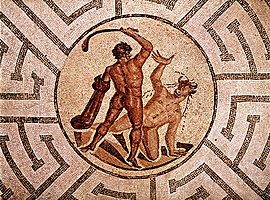

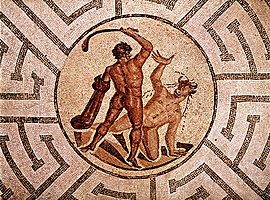

Remember the story of how Theseus found his way out of the labyrinth after fighting the Minotaur by following the thread of Ariadne?

In a similar way, “storylines” will help exhibit visitors thread their way through Galileo’s World.

Storylines make the exhibit come alive

The exhibition is far too large to do or see everything in a single day. One day a visitor might choose to experience it according to an astronomy storyline; the next occasion they might follow it through with a music storyline, or devote themselves to the storyline of a particular gallery, and so on. Astronomy students and musicians and middle-school classes will not need to see and do the same things. We hope that visitors will return to the exhibit repeatedly to experience it via multiple storylines.

Each Storyline revolves around a dramatic character

The exhibition interweaves the storylines of various dramatic characters, interesting personalities who anchor stories and give them direction and shape. A dramatic character is the leading actor of a storyline, the main character of a drama. Just as writers for a television show develop each episode around the characters played by the leading actors, so we will develop the Galileo’s World storylines around major characters, so that visitors’ experience of the exhibition will be dynamic and engaging.

“Waystations” are the building blocks of Storylines

“Waystation” refers to an occasion for any kind of learning activity that is cast into the context of a narrative story or journey. (Waystation is also parallel to Reading Station, Instrument station, etc.) The first level of development for each gallery and working group is to focus on identifying and creating “waystations” – points at which visitors and students might pause for exploration and discovery.

Waystations exhibit the interactive principles discussed below to foster a visitor’s sustained engagement with a particular gallery and to add color to the various storylines which pass through that gallery. For example, a waystation in the Telescope gallery devoted to the drawing of the mountains on the Moon as they appear through Galileo’s replica telescope and comparing them with Galileo’s own depictions in the Sidereus nuncius might be of interest to many storylines, including astronomy, painting and the visual arts, and secondary science education.

After identifying waystations, then, for each gallery and for some of the working groups, we will combine select waystations into storylines.

“Waystations” anchor lesson plans and specific learning activities

Each waystation is associated with learning activities, video modules, instrument tutorials, etc. After identifying a waystation, then (moving downscale) we can begin to collect and/or develop the lesson plans to associate with it, in collaboration with educators, amateur astronomers and other partners. Waystations provide us with a conceptual way to consolidate a group of lesson plans and activities into a single node, where instructors can choose the activities most appropriate to their group.

Storylines feature two types of dramatic characters

Any beautiful plaid consists of colored fabric laid in two directions, the warp and weft:

The combination of only a few colors, overlain in warp and weft, produce a myriad of hues, rich and deep and distinctive. The synergy between warp and weft multiplies rapidly: only six base colors produce a total of twenty-one different hues!

Just as fabric in a plaid is laid in two orientations, warp and weft, so we have two varieties of storylines, and two kinds of dramatic characters: hosts and guides.

Just as the rich potential hues of a plaid result from a few colors criss-crossing back and forth, so, when visitors engage the exhibit through the storylines of only a few hosts and guides, their experience will become as rich and multifaceted as any Scottish plaid.

Hosts

Each gallery tells a story with one major theme. A host represents a gallery and introduces each gallery’s major theme. Most galleries will have their own unique host. The host actor/actress, in full costume, will usually personify one of the authors of a book in its gallery, or a contemporary, and offer insight into the story of the gallery. The host is the warp of the exhibition plaid.

- Gallery Introduction: Each gallery host will provide a 2-3 minute video introduction to the gallery theme.

- Gallery storyline: A host may also give a visitor the option of pursuing a gallery-specific storyline featuring dramatized authors of the books on display who elaborate on specific topics related to the gallery theme. For instance, the Galileo and China gallery may have its own storyline.

- Gallery waystations: Each gallery section has a Waystations page for various learning activities. The gallery host will introduce not only the books on display in a particular gallery, but also the associated learning activities or waystations. A waystation lies at the intersection of the warp and weft of the exhibition, associated with a particular gallery storyline but also utilized in one or more criss-crossing storylines.

Guides

A guide embodies a storyline customized for a particular interest or age-group. A guide escorts each target audience through the exhibition, from gallery to gallery. A guide is the weft of the exhibit plaid.

- Guides are usually fictional characters, but historically representative of a particular place and time. For example, the guide for an astronomy storyline might be a fictional friend of Galileo’s who assisted him with his telescopic discoveries, and has “inside” information he heard from Galileo himself about various other figures and episodes he may comment on.

- Guides will convey visitors from one gallery host to the next, and provide context in which each gallery host’s comments will make the most sense to the particular group (skipping some galleries or substituting their own briefer comments for those of some gallery hosts).

- Guides for different storylines will stop at different waystations, even in the same galleries, leading visitors to engage the story of the exhibition using different combinations of learning activities.

- Guides need not be unique; Working Groups are free to collaborate in order to create a dramatic character with fuller character depth. For example, the astronomy and physics Working Groups might decide to develop a single guide character for both of their storylines, or they may prefer to use a different guide for each storyline.

How will storylines work?

Storylines connect various galleries and waystations by placing them in context, within a coherent narrative that adds drama and a dynamic dimension so that visitors experience the exhibit as a journey. There are various mutually-reinforcing ways visitors will experience the exhibit storylines:

- Storylines will feature in-costume video shorts. These videos will be produced with collaboration from the drama and theater departments. They will be displayed on kiosks at each gallery, or flat panels, and/or on the iPads that visitors may carry with them throughout the exhibit.

- Storylines provide guidance to docent educators as they lead classes in the exhibit. A docent might structure the tour around a particular storyline. A docent might choose to display some of the host’s video shorts on an iPad or flat panel display. Sometimes a docent might even dress in costume.

- Storylines also will organize the companion website according to particular themes and age groups. (See the “Academy of the Lynx website” section below.)

Visitor strategies

Visitors may be adopt various strategies to engage the exhibition:

- Overview: A minimal, hour-long orientation to the exhibition might consist merely of viewing the galleries, introduced by the brief gallery video introductions, along with a visual survey of the books. An overview of this sort will be provided by a special storyline called “The Galileo Code.”

- Gallery-specific storyline: One might also devote oneself to experiencing the storyline of one particular gallery.

- Guide-specific storyline: Visitors or classes might be escorted through the exhibit via a storyline of topical interest, such as astronomy or music, stopping by a select number of waystations as they travel through a select number of galleries most relevant to the topical storyline.

- Plaid: More than one of the above in any combination, or returning on more than one occasion.

How will we create the Host and Guide dramatic characters?

Waystations:

- One way to create dramatic characters for guides is to first think about the learning activities, or waystations, for a particular working group. Waystations are the building blocks of guides and storylines. Once a few waystations are determined, then one can begin to imagine the sort of dramatic charactert can connect the waystations in a dramatic story.

- Develop every waystation in light of its storyline potential, so that it will be engaged as part of a larger dramatic context.

- The nature of any emerging storyline may prompt ideas for creating additional desired waystations.

- When constructing a dramatic character and storyline, include a mixture of different kinds of waystations. Consider the types of challenges, puzzles, games, interactions, and rewards that might make a journey through the exhibit according to that character’s storyline more participatory and interactive (see next section).

- Not every working group needs to create a guide or storyline; some working groups may decide merely to create some waystations (learning activities) to be used by other guides within other storylines.

- See the Waystations list.

Gallery storylines: Each gallery site contains a host storyline page. On the storylines page for any particular gallery, anyone can leave notes and tips for various dramatic characters, whether hosts or guides. That is, leave notes and tips for the writers of guide characters to keep in mind when their guides approach that particular gallery. Perhaps one kind of note or tip would describe a particular waystation being created by a working group that might be of interest to other storylines crossing through that gallery. Gallery storyline pages are for gallery-specific tips only; the learning activities and scripts for guides will be found on the pages for working groups.

Guide storylines: Guide characters will be created by working groups. If you want to create a guide for a particular audience or theme, first create a working group. On your working group site, create a page to begin characterizing the guide personality and drafting the storyline. Create a character profile such as this:

|

Name:

|

name

|

|

Gender:

|

|

|

Age:

|

|

|

Dates:

|

|

|

Personality traits:

|

|

|

Storyline description:

|

|

|

Reward:

|

|

Eventually write up a script for the storyline that can be used by the actor or actress who will record the video in costume to be included on iPads and iPhones. The dramatic character will be used as the basis for live tours by docent educators. Each working group should recruit some educators to create the waystation learning activities for the group’s storyline. Working group educators will also be invited to train docents, give tours, and create a blog and social media accounts for the guide that will be published on the Academy of the Lynx website (see below).

Each working group can decide whether to create their own storyline or merely to contribute learning activities or waystations that can be “visited” by other storylines. To create a storyline rather than a waystation will involve a greater and ongoing commitment (see the Academy of the Lynx section below). But some of the storylines worthy of that commitment may be:

- Elementary science education

- Middle school science education

- Secondary science education

- Astronomy

- Music

- Mathematics

- Painting and visual arts

- Travel

- Physics

- Natural History

- Science and religion

- Overview (The Galileo Code)

We will have to choose carefully which dozen or so storylines to create, depending on our volunteer developers’ interests.

Engagement: How do storylines enhance the experience of visitors?

In the Galileo’s World exhibition, we intend to engage visitors with meaningful and memorable experiences. The host and guide storylines are our prime means of achieving these dimensions of visitor engagement. In the context of storylines, visitors will stop at various waystations. The result will be a visitor experience characterized by the following:

- Stories: Science is a story. We want to reiterate this in creative ways. Similarly, stories convey meaning more memorably than didactic instruction. Storylines therefore play a central role in casting a visitor’s experience of the exhibition in the context of a narrative story.

- Participation: By participation, we mean that the exhibition will engage visitors to construct meaningful experiences for themselves. By touring the exhibition with a select guide, visitors will feel like they are participating in Galileo’s World in a more dramatic and meaningful way. Participation is very similar to the aspect of co-creation (next).

- Co-creation: Visitors learn by creating knowledge, drawing connections for themselves, constructing meaning in their own frames of reference. Our approach to this exhibit will encourage visitors to translate Galileo’s World into their own world. We will seek to make our visitors co-creators of knowledge, rather than seeking only to impart authorized information to them according to our own frames of reference. We want to emphasize what visitors can do with the knowledge they gain in a participatory way, so that it will be memorable and meaningful to them. This approach is more like a Montessori school, in which we provide joyful opportunities via waystations for visitors to create their own learning experiences in a self-directed and open manner. It is not to be a didactic lecture hall of the sort epitomized by John Houseman in The Paper Chase!

- Challenge: Hard-won experiences are remembered best. We want to find a way to challenge every visitor of the exhibition. Many will find a piece of missing context that makes intelligible some otherwise confusing excerpt from a primary source. For some, the nature of the challenge may involve the intellectual work of identifying and casting away some uncritical preconception. For others, it may involve constructing an unexpected connection never recognized before between two areas of personal interest. In practice, a challenge may be as simple as solving a puzzle at a particular waystation, or finding clues in one gallery, or distributed among several waystations, to complete a game level on an iPad before moving on to the next. For everyone, we hope to engage their creativity and resourcefulness to solve a problem that makes the exhibit more meaningful to them. We hope no one will leave the exhibit without having met and conquered a challenge of some sort.

- Interaction: Interactivity means more to us than having touch screen electronic devices or watching animated page curls. Hands-on activities are very helpful, but they will count as interactive only when they are active and not merely passive activities. For example, instruments provide one form of interactivity when they are actually used by visitors, hands-on, with the opportunity to record their results and compare them with the historical record (as in drawing the Moon as seen through Galileo’s replica telescope, then comparing it with Galileo’s depiction, and the depictions of other visitors; or similarly with observations made through a microscope). But interactivity can also mean any kind of active rather than passive engagement, as in the challenge of solving a multi-step puzzle while working through a gallery, before moving on to the next gallery, as if one were moving to the next level of a video game.

- Persons: Interactivity also refers to interaction with other persons at various waystations, either virtually (as in competing for highest scores) or tangibly (viewing products created by other visitors, or making decisions with companions, classmates, or others just happening to move through at the same time). How can people share their stories of what made their journey through the exhibit meaningful to them? We want the experience of the exhibit to be personal, and this is also what interactivity means for us.

- Rewards: What can visitors take away from the exhibit? Let’s give them something specific and satisfying, whether tangible or virtual. We can be creative with this, but let’s give some thought to the possible kinds of rewards we might offer. Visitors who engage in our storylines should earn rewards of some sort for their efforts in knowledge creation, overcoming challenges, puzzle solving, etc. Tangible rewards might range from displaying the product of their work at a particular waystation, to receiving patches, artistic prints or postcards, to earning the opportunity to print a 3-D object (e.g., a replica telescope). Virtual rewards might consist of signing their name in the electronic guest-book, which randomly broadcasts previously entered names on a bulletin board, or seeing their name displayed after winning a high score in a competitive game. A typical reward might be the opportunity to get their photo taken with the guide using a special background in Photo Booth, or a Souvenir Penny.

Academy of the Lynx website

Each of the above hosts and guides, along with their storylines, can be made more “real” by the use of social media, coordinated from the Academy of the Lynx website for educators. That is, we will ordinarily expect that each guide character will communicate with followers (and each other) through twitter, facebook and pinterest, and will maintain a blog.

Check out the blog of Dr. Watson in support of the BBC TV series Sherlock for an example of this kind of use of social media to make the exhibition world more real and engaging.

When creating a guide (or a gallery host), consider what kind of personality they will display on the blog and in social media. Are they male or female? What kind of sense of humor do they have? How old are they? Create a profile so that dramatic characters will not all be the same! They should each have a distinctive personality and voice.

We will recruit educators to write posts on each dramatic character’s blog, twitter and Facebook, and to respond to student and public comments made on the blog. The storyline blogs will be aggregated and made accessible via the Academy of the Lynx companion website, where comments by students and others will be responded to by educator docents, as often as possible using the distinctive voices of the guides.

Website: lists, links, tags

- This page has child pages to list characters (hosts and guides), waystations, and their storylines. Please add to these lists any waystations, guides or storylines that you work on and link them to the relevant pages in your working group.

- Please tag any pages throughout this site that are related to dramatic characters, hosts, guides or storylines with the storylines tag. Please tag pages related to learning activities with the waystations tag.

———————

(search for “OU Lynx”). They are being created in various topical series, and linked to the Galileo’s World exhibit by gallery and subject. Series titles include: Iconic Images; Instruments and Experiments; Starting Points for discussion; Primary Source excerpts; 2-minute stories; Stand-up activities; Constellations; and Women in Science.

(search for “OU Lynx”). They are being created in various topical series, and linked to the Galileo’s World exhibit by gallery and subject. Series titles include: Iconic Images; Instruments and Experiments; Starting Points for discussion; Primary Source excerpts; 2-minute stories; Stand-up activities; Constellations; and Women in Science.